Say hello to…

Say hello to…

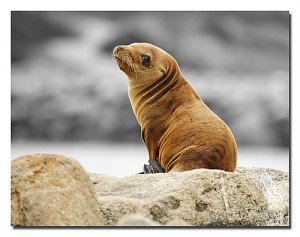

the California Sea Lion!

(Zalophus californianus)

The California Sea Lion is a coastal sea lion of western North America. Their numbers are abundant (188,000 U.S. stock 1995 est.), and the population continues to expand at a rate of approximately 5.0% annually. They are quite intelligent, can adapt to man-made environments, and even adult males can be easily trained. Because of this, California sea lions are commonly used for entertainment in circuses, zoos and marine parks; and are used by the US Navy for certain military operations. This is the classic circus “seal”, despite the fact that it is not a true seal.

California sea lions grow to 300 kg (660 lb) and 2.4 meters (8 ft) long, while females are significantly smaller, at 90 kg (210 lb) and 2 meters (6.5 ft) long. They have pointed muzzles, making them rather dog-like in appearance. Males grow a large crest of bone on the top of their heads as they reach sexual maturity, and it is this that gives the animal its generic name (loph is “forehead” and za- is an emphatic; Zalophus californianus means “Californian big-head”). They also have manes, although they are not as well developed as the manes of adult male South American or Steller sea lions. Females are lighter in color than the males and pups are born dark, but lighten when they are several months old. When it is dry, the skin is a purple color. A sea lion’s average lifespan is 17 years in the wild, and longer in captivity. By sealing their nose shut, they are able to stay underwater for up to 15 minutes.

As its name suggests, the California sea lion is found mainly around the waters of California. It also lives around Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia to the north and Mexico to the south. The Galápagos Sea Lion and the extinct Japanese Sea Lion were once considered subspecies of the Californian sea lion. Now these two populations are generally considered as distinct species.

California sea lions breed from the Channel Islands off Southern California to Mexico. Major breeding sites are San Miguel and the San Nicolas islands. Non-breeding populations live as far north as British Columbia.

California sea lions prefer to breed on sandy beaches in the southern part of their range. They usually stay no more than 10 miles out to sea. On warm days they stay close to the water’s edge. At night or on cool days, the sea lions will move inland or up coastal slopes. Outside of the breeding season they will often gather at marinas and wharves and may even be seen on navigational buoys. These man-made environments provide safety from their natural predators; orcas and white sharks.

California sea lions prefer to breed on sandy beaches in the southern part of their range. They usually stay no more than 10 miles out to sea. On warm days they stay close to the water’s edge. At night or on cool days, the sea lions will move inland or up coastal slopes. Outside of the breeding season they will often gather at marinas and wharves and may even be seen on navigational buoys. These man-made environments provide safety from their natural predators; orcas and white sharks.

California sea lions can also live in fresh water for periods of time. They feast on Pacific salmon in front of Bonneville Dam, 146.1 river miles from the Pacific Ocean. Historically, sea lions hunted salmon in the Columbia River as far as The Dalles and Celilo Falls, 200 miles (320 km) from the sea, as remarked upon by people such as George Simpson in 1841. In 2004, a healthy sea lion was found sitting on a road in Merced County, California, almost a hundred miles upstream from San Francisco Bay and half a mile from the San Joaquin River.

California sea lions feed on a wide variety of seafood, mainly squid and fish; sometimes even clams. Commonly eaten fish and squid species include salmon, hake, Pacific whiting, anchovies, herring, schooling fish, rock fish, lamprey, dog fish, and market squid. They feed mostly around the edge of the continental shelf as well as sea mounts, the open ocean and the ocean bottom. Average annual food consumption of males in zoos increases with age to stabilize at approximately 4,000 kg (8,818 lbs)/year by the age of 10 years. Females showed a rapid increase in average annual food consumption until they were 3 years old. Thereafter, females housed outdoors averaged 1,800 kg (3,968 lbs)/year.

California sea lions may eat alone or in small to large groups depending on the amount of food available. They will cooperate with dolphins, sharks, and seabirds when hunting large schools of fish. Sea lions from the state of Washington will wait at the mouths of rivers for the salmon run. They also have learned to feed on steelhead and white sturgeon below fish ladders at Bonneville Dam and at other locations in the Columbia River, Willamette River, and in Puget Sound.

California sea lions may eat alone or in small to large groups depending on the amount of food available. They will cooperate with dolphins, sharks, and seabirds when hunting large schools of fish. Sea lions from the state of Washington will wait at the mouths of rivers for the salmon run. They also have learned to feed on steelhead and white sturgeon below fish ladders at Bonneville Dam and at other locations in the Columbia River, Willamette River, and in Puget Sound.

Adult females forage between 10 and 3000 km from the rookery and dive to average depths of 31.1 to 98.2 m, with maximum dives between 196 and 274 m. They travel at an estimated speed of 10.8 km/h, and young sea lions have an initial defecation time averaging 4.2 hours. Adult females spend 1.6-1.9 days on land and 1.7-4.7 days at sea.

California sea lions are highly social and breed around May to June. When establishing a territory, the males will try to increase their chances of breeding by staying on the rookery for as long as possible. During this time, they will fast, using their blubber as an energy store. Size is a key factor in winning fights and well as waiting. The bigger the male the more blubber he can store and the longer he can wait.

A male sea lion can only hold his territory for up to 29 days. Females do not become receptive until 21 days after the pups are born, thus the males do not set up their territories until after the females give birth. Most fights occur during this time. Soon, the fights go from violent to ritualized displays such as barking, roaring, head-shaking, stares, and bluff lunges. There can be as many as 16 females for one male. For adult males, territorial claims occur both on land and underwater. They have even been known to charge divers who enter their underwater territory.

A male sea lion can only hold his territory for up to 29 days. Females do not become receptive until 21 days after the pups are born, thus the males do not set up their territories until after the females give birth. Most fights occur during this time. Soon, the fights go from violent to ritualized displays such as barking, roaring, head-shaking, stares, and bluff lunges. There can be as many as 16 females for one male. For adult males, territorial claims occur both on land and underwater. They have even been known to charge divers who enter their underwater territory.

The females have a 12-month reproductive cycle, 9-month actual gestation with a 3-month delayed implantation of the fertilized egg after giving birth in early to mid-June. Mothers may give birth on land or in water. The pups are born with their eyes open and can vocalize with their mothers. Pups may nurse for up to six months and grow rapidly due to the high fat content in the milk. California Sea Lions, along with other otariids and walruses, are possibly the only mammals whose milk does not contain lactose. At about two months the pups learn to swim and hunt with their mothers.

After the breeding season, female California sea lions normally stay in southern waters while the adult males and juveniles generally migrate north for the winter. Social organization during the non-breeding season is unstable. However, a size-related dominance hierarchy does exist. Large males use vocalization and movement to show their dominance and smaller males always yield to them. Non-breeding groups are gregarious on land and often squeeze together. Most sea lions found in man-made environments are males or juveniles, because sea lions don’t breed there and it is mostly those groups that migrate to those places during the non-breeding season.

California sea lions are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act in the United States. However their population has been increasing and conflicts with humans and other wildlife has increased. California sea lions have damaged docks and boats, stolen fish from commercial boats, and have attacked and injured swimmers in San Francisco Bay. Because of this, they have been shot at by locals and fishermen.

In 2007, legislation was introduced (HR 1769: Endangered Salmon Predation Prevention Act) that would amend the Marine Mammal Protection Act to permit lethal California sea lion removal from near salmon runs when their population exceeds a determined maximum sustainable level. The purpose of HR 1769 is to relieve pressure on the precipitously declining salmon populations of the Pacific Northwest. Officially, pinnipeds account for only an estimated 4% of salmon loss in 2007. However, the 4% predation number comes from actual observation of predation; because much of the predation occurs underwater, marine biologists believe that the true rate is far higher.

In 2007, legislation was introduced (HR 1769: Endangered Salmon Predation Prevention Act) that would amend the Marine Mammal Protection Act to permit lethal California sea lion removal from near salmon runs when their population exceeds a determined maximum sustainable level. The purpose of HR 1769 is to relieve pressure on the precipitously declining salmon populations of the Pacific Northwest. Officially, pinnipeds account for only an estimated 4% of salmon loss in 2007. However, the 4% predation number comes from actual observation of predation; because much of the predation occurs underwater, marine biologists believe that the true rate is far higher.

Short of lethal removal, attempts have been made to identify California sea lions that are aggressive salmon predators and to relocate these members from the area near salmon runs. However, relocation generally fails as the sea lions simply return. In January 2008, at the request of Washington and Oregon, the National Marine Fisheries Service has drafted a proposal to euthanize approximately 30 animals annually at Bonneville Dam. The Humane Society threatened a lawsuit. In response, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled for the animals to be removed but not killed.

From the Humane Society court case – NMFS’s decision to authorize the killing of native, federally protected animals that are having a documented 0.4 to 4.2 percent impact on the spring salmon run is impossible to reconcile with: (1) NMFS’s 2005 decision finding that fishermen’s annual take of up to 17 percent of listed salmon is not significant and has only ‘minimal adverse effects on Listed Salmonid ESUs in the Columbia River Basin;’ (2) the States’ 2008 decision to increase fishing quotas from 9 percent to 12 percent of the total spring run; and (3) NMFS’s 2007 decision finding that hydroelectric dam take up to 60 percent of listed juvenile salmonids and up to 17 percent of listed adult salmonids ‘meet[s] or exceed[s] the objectives of doing no harm and contributing to recovery with respect to the ESUs.'”

taken from Wikipedia

Phone / Email

Phone / Email RSS Feed - Blog

RSS Feed - Blog Facebook

Facebook

![GetAttachment[2].jpg](/wp-content/uploads/wppa/329.jpg)